Lipstick vs. The Ayatollah

by Monica Zandi

Women’s Taxi, Randy Goodman, 2015. Photography. Images courtesy of Randy Goodman.

In a country that mandates veiling, Iranian women experience a myriad of constraints placed on them by both the state and society. But despite being denied the right to visibly express creativity or uniqueness, one way Iranian women continue to push for individuality and personhood is by expressing themselves outwardly through chic fashions. In an exhibit at the Bronx Museum entitled Iran: Women Only, images of Iranian women are presented from Randy H. Goodman’s press and freelance archives that challenges the essentialism pervading the Western image of Iran while generating discourse on the country’s culture of gendered resistance.

Goodman’s work, both early and later, is that of an outsider pursuing sociological inquiry and newsworthy events. In the 1980s, she captured mostly religious Iranian women belonging to a lower socioeconomic strata supporting the revolution. But in 2015, she captured modern women in everyday situations amidst the backdrop of U.S.-Iran nuclear negotiations (2015). Inside the last two rooms of the exhibit, small and medium format photographs from 2015 show Tehrani women driving cars, laughing in museums, and wearing makeup. These photos hang alongside press photos from the Hostage Crisis (1979) and Iran-Iraq War (1980-88) that she shot while on assignment for CBS News and Time Magazine.

In the newer photos of everyday life, Goodman conducts an ethnographic exploration of the mundane ways in which Iranian women go about their daily lives. Mining her archive some forty years later, Goodman, whose motives are unstated in the actual exhibit, appears to be contrasting these pictures to her earlier photojournalism focused on scenes like mobs of supporters of the revolution which caters to a western audience’s stereotypes about veiled Muslim women. In an interview, Goodman noted that the exhibit was originally going to include post-cards and an audio component to provide greater context about the press photos from the 1980s, which at the time were taken to give audiences a view of how empowered and anti-colonial religious Iranian women felt during the Revolution.

The exhibit presents public life during three critical flashpoints in Iran’s history: the Hostage Crisis, Iran-Iraq War, and U.S.-Iran nuclear negotiations. Photos from the past and present are juxtaposed with one another to present the viewer with a sense of change, thereby challenging their assumptions and entrenched worldviews about Iran.[1] In Khomeni Supporter (1983), an aging Muslim woman in an all-black chador (the head-to-toe black veil) stares into Goodman’s camera while holding up a picture of Khomeni; next to it, Exercising (2015) features a smiling middle aged woman using a park elliptical, while donning lipstick, a tight unbuttoned beige coat, colorful veil, designer sunglasses, and striped pink sneakers. Both photographs engage with each other and the viewer. The viewer can thus reflect on his or her understanding of Iranian women in observing the stark differences. While the former image may evoke stereotypes about Iranian women as oppressed victims of Islamic patriarchy, the latter demonstrates the subtle ways in which Iranian women have subverted the constraints placed on them. When I conversed with Goodman, she noted that an American spectator from the state of Georgia told her after viewing the exhibit that she “did not know Iranian women were allowed to dress like that and presumed they all wore burqas.”[2]

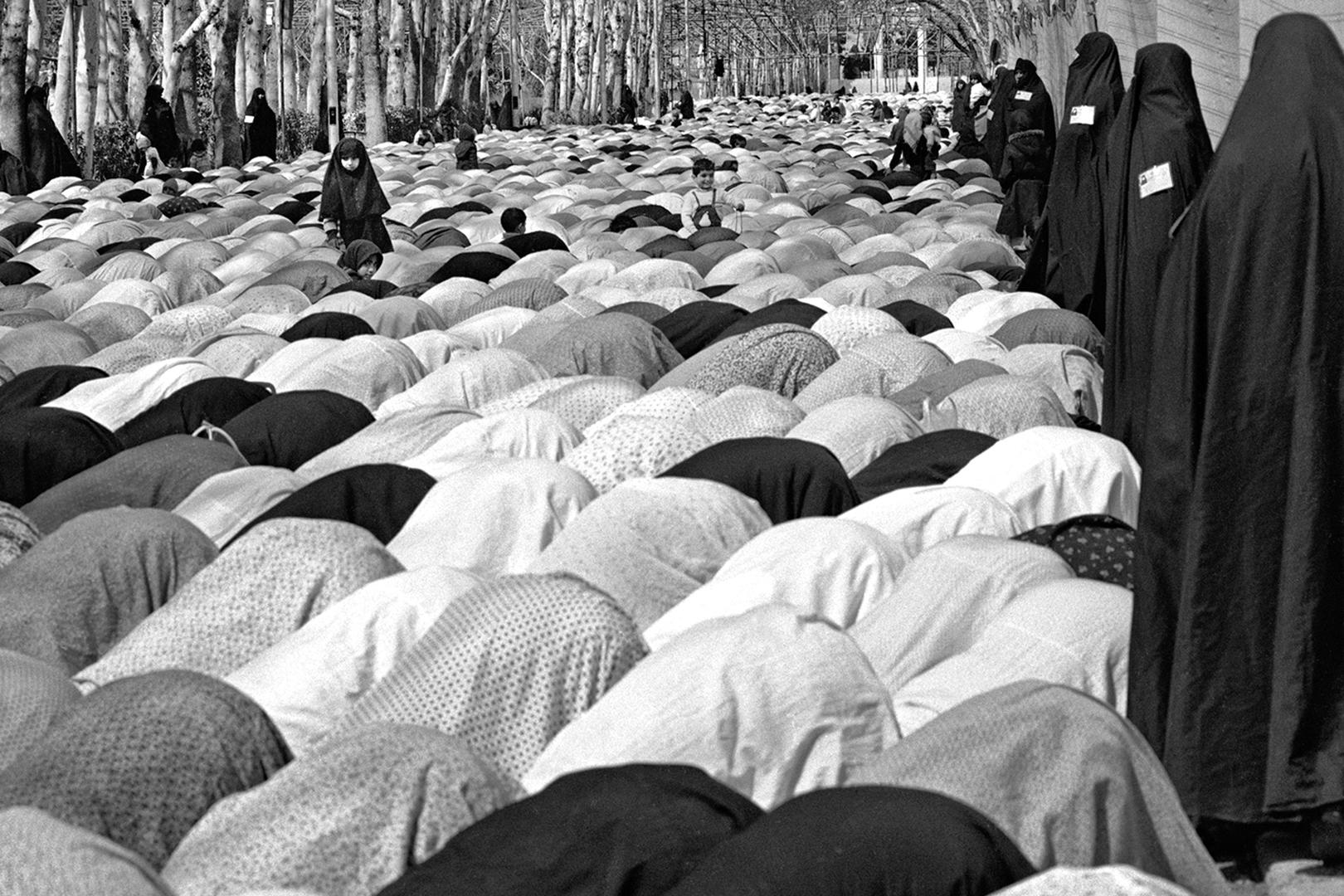

Although her early work emerged from a sincere desire to convey the anti-imperialist mood of post-revolution Tehran and understand the ongoing change there, Goodman sold these photographs without any personal input from the subjects, or context for audiences. She admitted this was a stake, noting that she still regrets it nearly forty years later. Herein lies the exhibit’s curatorial challenge—Iran: Women Only lacks her personal narrative or clues as to her motivation during hear early work. This omission lends itself to potential misinterpretation, particularly of the press photographs. Without this context and personal narrative, it is difficult to interpret Goodman’s role as a mainstream press photographer and her anti-colonial objectives during the Hostage Crisis. To the viewer, her press photos from the 1980s could easily bleed into familiar visual vocabularies about Iran that evoke the ‘terrorist,’ ‘Other,’ ‘radical,’ and a ‘backwards’ society.[3] Goodman states her photographs were snapshots of newsworthy events (e.g., protests, demonstrations, prayer services) meant to show Iran’s political shift in the early 1980s. Her exhibit, she notes, is not intended to be viewed as an “art show” but rather as documents from Iran’s past and present historical canons. While she did not intend to create mediated narrative, the exhibit does not clarify these intentions, potentially leaving audiences confused as to how these images should be interpreted alongside the more recent photos in the exhibit.

These newer photos are the result of Goodman’s 2015 return to Iran. On this trip, she had no media backing or publication goals; but sought to produce new images featuring Iranian people in dialogue with her press photos. Goodman unequivocally demonstrates how Iran’s political atmosphere is different now through the exhibit’s dialogical and pedagogical register. By using women as evidence of Iran’s change, her exhibit tackles issues pertaining to them such as stereotypes about Muslim identity and compulsory veiling. In the 2015 images, the audience gains a greater sense of liberation felt yet in the 1980s images—lost due to lack of context. When one sees a chador-clad Muslim woman in a black and white photograph from a religious demonstration supporting Ayatollah Khomeni, the meaning of her presence is transmuted; in that moment, she was empowered, but forty years later, she is perceived as ‘oppressed’ or ‘radical’ by western audiences.

The positioning in Goodman’s freelance pictures from 2015 to press photos from CBS, Time Magazine, and Gamma Liason conjures mainstream media's habit of generating mediated visuals; where photographs are utilized by media institutions to fit a particular narrative or ideology. The press photos represent Iran’s history through the lens of geopolitical developments seen on popular television and front papers. While taken for historical documentation, Goodman’s press photos nevertheless evoke familiar graphics, ingrained in our collective memory since the Hostage Crisis. In Women’s Day Demonstration with Posters (1983) and Women’s Day March (1983), both photos feature hordes of black-clad, faceless, Iranian women holding posters of Khomeni. Again, the exhibit does not provide much context about these women or the moment they occupy—let alone any clear language, feminist or anti-colonial, in a way that breaks stereotypes about Iran while also highlighting how news organizations perceived these images through Western Eurocentric paradigms to prove an essential difference between Iran and the West, perpetuate Orientalist tropes, and further damage Iran’s identity as a result of the Hostage Crisis.

However, while the exhibit does not address how mainstream Western society ‘Othered’ and subordinated the chador-clad women of the 80s after their stories entered the canon, we see an attempt to counter Iran’s mediated treatment in the news with the newer series. In Women’s Taxi (2015) and Tehran Bazaar (2015), for instance, Iranian women appear exercising greater degrees of agency. Here, the subjects are active compared to their passive counterparts in Goodman’s press photographs, where the chador-clad women appear as having only an “Islamic” identity. When Khomeni rose to power, he used religion and state control to impose a conservative Islamic proscriptions of female identity on Iranian women. All traces of makeup or “Western” style clothing disappeared from public life. Over the years, women seeking such images would need to resort to illegal means such as satellite television and social media.[4] Thus, by wearing make-up and showing strands of hair, the women in Goodman’s photos challenge both the official Iranian state-mandated female identity as well as Western assumptions that Iranian women are silent victims. Women’s Taxi shows a middle-aged woman, smiling proudly as she drives a women-only taxi cab, wearing makeup and a loose veil exposing locks of hair stiff from hair spray. Next to it, Tehran Bazaar shows a trio of Iranian women shopping for colorful accessories, wearing loose veils and colorful blue coats, sporting cosmetic surgeries. These images reveal women subtly opposing the regime’s mandate on veiling and expectations for women.

While the exhibit goes some distance in introducing nuance to the portrayal of Iranian women, there is room for a deeper exploration of western photojournalism’s impact on how iconic images inform the audience’s political awareness and cement stereotypes. Goodman could benefit from conceptually or didactically providing the audience with more personal knowledge about her travels to Iran, opinions on journalism, and how she developed her images. Further, while the exhibit picks up visual symbols of Iranian women’s resistance, e.g., colorful veils and makeup, it does not delve further into how, why, and what historical triggers or social forces made way for this resistance. Deeper dialogue with the subjects is also absent—what is the female taxi driver’s story? What about the exercising woman? These questions and gaps highlight what seems missing in an exhibit highlighting the agency of Iranian women: the participation, consultation, or inclusion on some level of Iranian artists or photojournalists. Goodman’s role as an American photojournalist in Iran on one hand wanted to present historical documents and newsworthy events from anti-imperial, empowered women in the 1980s. On the other hand, selling such images without her voice is an important tension related to the discourse about women in Iran in mainstream media. But in order to artfully navigate the nuances of Iranian identity, Iran: Women Only, would benefit from featuring the inclusion of creators closer to the subject—Iranians— in future reiterations.

[1] Michael Christie, et al, Putting transformative learning theory into practice. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 55, 2015, 10-13.

[2] In a conversation with Randy Goodman (Monica Zandi 2018, oral communication, 1st November).

[3] Corsica, The Fateful Fifty-Two, 33.

[4] Marizeh Kaivanara, “Beauty in Iran: Paradoxical and Comic,” Beauty Demands, 2017.

Monica Zandi is a writer, educator, and artist by way of Iran. She has written for Sublet Projects, Kaltblut Magazine, and Feminist Wednesdays on a range of topics such as art from the 18th century and collage from local Brooklyn artists. Her current focus is on analyzing the impact of hyper-reality on contemporary Iranian feminist thinking and art.