The Body of a King

by Samuel Tafreshi

“The shadow of god became the humiliation of god!”

What is to be done with the body of a king? When all of the meaning and majesty imbued in his person shrivels and fades before the world, what does he become? Inherently political, it is the very constitution of the body that grants him his power. His birth and his death are not simply natural processes, but signal the transformation of the state. So what is to be done with this body—as politicized and saturated with significance as it is—when it ceases to have agency?

**

On July 28th, 1980, former President Richard Nixon and deposed King Constantine II of Greece arrived in Cairo to attend a modest funeral at the Al-Rifa’i Mosque. The crowd included a small but memorable guest list: Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat, the two previously mentioned former heads of state, a spattering of ambassadors, and several members of the Pahlavi royal family. They had been the few who had come to pay their respects and bury the deposed Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the fourth and final king of Iran to die in exile. Mohammad Reza Shah had ruled Iran for nearly forty years, but after being overthrown by the 1979 revolution he died a disgraced monarch far from his homeland.

***

“Arrest, execution: Who is in line?”

A year and a half earlier in January 1979, Mohammad Reza Shah and Empress Farah Pahlavi stormed across a tarmac in Tehran trailed by a German Shepherd named ‘Beno’, a puppy named ‘Catsu’, and a small entourage of servants and security. The Pahlavi dynasty was on the brink of collapse. The Shah had appointed a nationalist Prime Minister in the hopes of appeasing the revolutionaries and he planned to depart Iran until his return to power could be ensured. The tide, however, had already turned against him. Many cities in Iran were under the de facto control of revolutionaries and in less than a month Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini would be greeted by a crowd of millions on the same tarmac.

The Pahlavis and their entourage boarded their private plane, Shahbaz, only to discover that most of the dishware and amenities had already been stolen by airport staff. Mohammad Reza, a trained pilot, entered the cockpit and reportedly flew the plane for the first hour towards Egypt. The next day, several Iranian newspapers excitedly reported, “The King Left!” (shah raft). Never to return, he would become the fourth consecutive Shah of Iran to die in exile.

The arrival in Egypt signaled the beginning of an 18-month saga that would take the Shah to six countries in hopes of receiving medical care or asylum and earn him the nickname ‘The Flying Dutchman.’ Mohammad Reza was told by the U.S. that he should travel first to Egypt, for diplomatic business, and then on to the U.S. for a more permanent stay. Sadat welcomed the Shah and apparently went to great lengths to make him feel like a king while he was in Egypt. Little did the Shah know, there was no diplomatic business in Egypt and there were no immediate plans for him to arrive in the U.S.

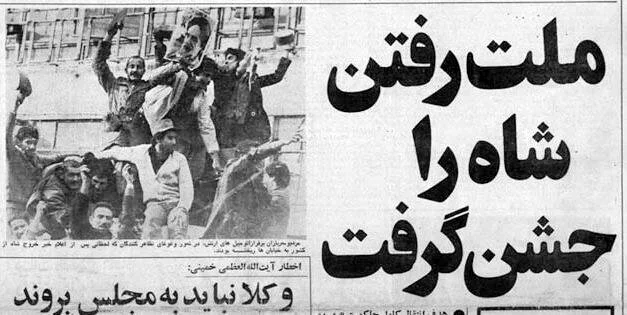

Jan 17th, 1979 - People Celebrate Shah's Departure

At this point, the Shah scarcely understood the reality of his situation. He had fled to Europe previously to wait out the results of the U.S.-U.K. sponsored coup that overthrew Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953. Following the coup, he returned from his European sojourn and was restored to power by his Western allies. It is not unlikely that he, and some of his supporters, believed this may happen again. But 1979 was not 1953, and it appears the Shah’s allies saw little use for a puppet king. As each day passed, he was less and less a political actor and more of a political object. Lacking agency of his own, he became something to be moved about and argued over. His movements and decisions still carried political consequences, but he was increasingly at the mercy of them rather than in control of them.

Once it became clear that he would not be continuing to the U.S. any time soon, the Shah decided to visit King Hassan in Morocco—a longtime ally whom the Pahlavi dynasty had given significant loans over the years. King Hassan quickly realized the Shah was more of a liability than a piggy bank and informed him that he must leave Morocco immediately. Morocco was to host an upcoming conference of Islamic nations and King Hassan was under enormous pressure from both Islamic leaders and his own intelligence networks to expel the Shah. As the Pahlavi entourage prepared to leave, Mohammad Reza came to realize that no country would receive him. Up until the last hours before his departure from Morocco, no state had agreed to grant him even a tourist visa.

April 7, 1979 - Ex-Premier Hoveida Is Executed In Iran - New York Times

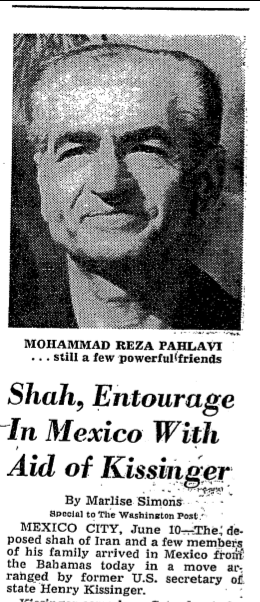

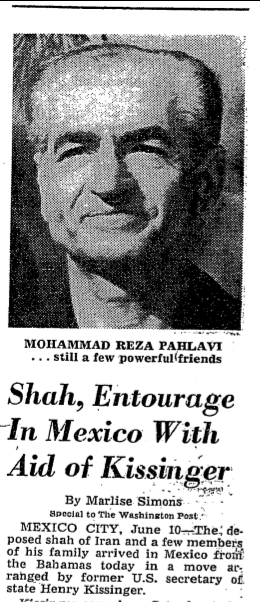

At the behest of the U.S. and U.K., the Bahamas issued a temporary stay visa. While on Paradise Island in the Bahamas, the Shah learned that many of his old regime—former and current heads of SAVAK, military officials, and former Prime Ministers—had been executed in Qasr Prison. The Shah slowly became aware of two things: he could never return to Iran and nowhere else would receive him. Over the next week, the Shah met with several diplomats, including former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, regarding asylum and was informed by his Western allies that they could not host him due to fears concerning security or oil interests. Although Kissinger could not offer asylum, he did push Mexico to accept him and campaigned on the Shah’s behalf in the U.S.

June 10th, 1979 - Shah, Entourage In Mexico With Aid of Kissinger - The Washington Post

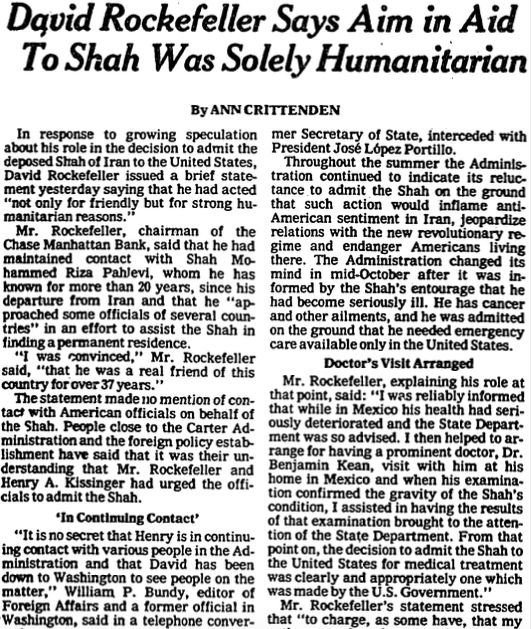

While the President and the State Department worried that granting the deposed leader entrance to the U.S. would provoke repercussions from the revolutionary government in Iran, there were many powerful individuals lobbying in favor of welcoming the Shah. Along with Nixon and Kissinger, the Shah enjoyed the support of David Rockefeller, Chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank. Rockefeller was perhaps his staunchest supporter and went so far as to send a private physician to examine the ailing monarch while he was in Mexico.

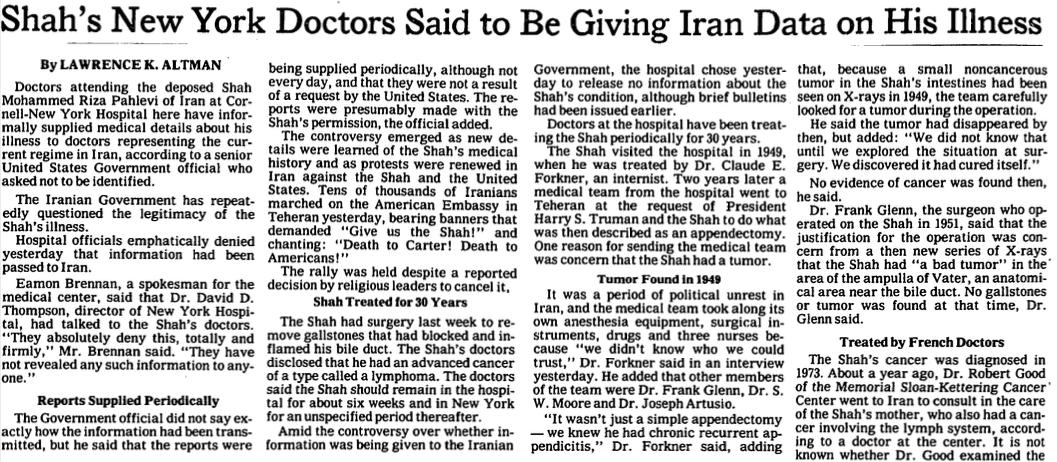

The physician announced that the Shah desperately needed access to U.S. medical treatment or he may die. Rockefeller stated that he believed the U.S. needed to support the king “not just for friendly reasons but for strong humanitarian reasons.” Other physicians concluded that the medical treatment required was available in Mexico but the Shah’s unwillingness to tell local doctors about his illness had led them to treat him for malaria instead of lymphatic cancer. Following Rockefeller’s announcement regarding the Shah’s health, Kissinger threatened to withhold much-needed support for Carter’s arms agreement with the USSR unless the U.S. admitted the Shah.

Ignoring continued warnings from the State Department, Carter finally acquiesced to the Shah’s entry on October 22nd, 1979. Under the cover of night, the deposed monarch touched down at LaGuardia Airport in New York City and was discreetly shuttled to New York Hospital. Despite the Islamic Republic of Iran’s calls for him to return and stand trial, as well as the looming threat of the seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Kissinger and Rockefeller had succeeded in strong-arming Carter into hosting Pahlavi.

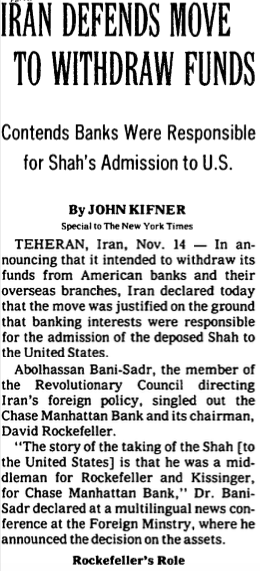

Although Rockefeller claimed that his support for the Shah was purely ‘humanitarian’, many have contended that his motives were far from virtuous. Chase Manhattan Bank–where Rockefeller was Chairman–had given Iran an ill-advised $500 million loan shortly before the downfall of the Pahlavi dynasty, and the revolutionary government had begun to withdraw from this account.

Nov 15, 1979 - Chase Bank Silent On Iran Statement - New York Times

Journalists and scholars have speculated that Rockefeller lobbied Carter to admit the Shah with full awareness that it would most likely lead to the seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran or another unanticipated violent action that would result in the freezing of Iranian assets. Abolhassan Banisadr, the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the interim government at the time, publicly accused Rockefeller and Kissinger of welcoming the Shah for exactly this reason. “The story of the taking of the Shah [to the United States],” Banisadr explained, “is that he was a middleman for Rockefeller and Kissinger for Chase Manhattan Bank.”

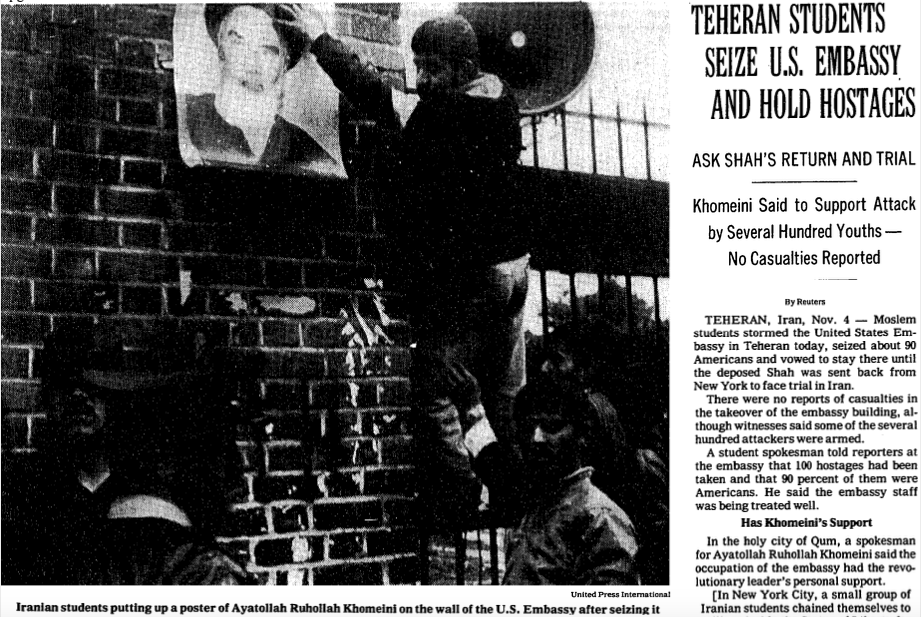

It is hardly surprising, in retrospect, that less than two weeks after the Shah arrived in New York the front page of the New York Times read: “Moslem students stormed the United States Embassy in Teheran today, seized about 90 Americans and vowed to stay there until the deposed Shah was sent back from New York to face trial in Iran.” The reaction to the Shah’s arrival and call for his return to stand trial, moreover, was not limited to Iran.

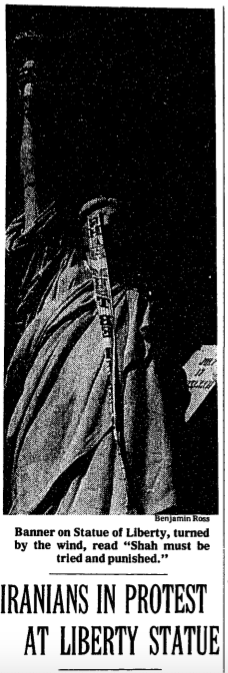

In New York City, a group of Iranian students chained themselves to the inside of the Statue of Liberty and hung a banner that called for the Shah to return. Protesters chanted “Death to the Shah” (marg bar shah) on the streets below his hospital room in New York City. Iranians across the U.S. called for the Shah’s extradition and were met with American counter-protestors calling for the deportation of Iranians and military action on Iran. Fighting broke out in Beverly Hills, California when a dozen Iranians calling for extradition were attacked by thirty-or-so counter-protesters. Concerned about escalating conflict in the Capitol, Carter banned federal permits for Iranian protesters in Washington D.C.

Dec 1st, 1979 - US Insists Shah Go - New York Times

Within a month of the embassy seizure, the government informed the Shah that he needed to leave the U.S. But the question of where arose once again. His preference was to return to Mexico, where he had lived before, but Mexico soon rescinded their offer for him to come. Mexico cited security concerns, but Queen Farah Pahlavi claimed that Cuba would only support Mexico’s bid for a seat on the U.N. Security Council on the condition that they refused the Shah refuge.

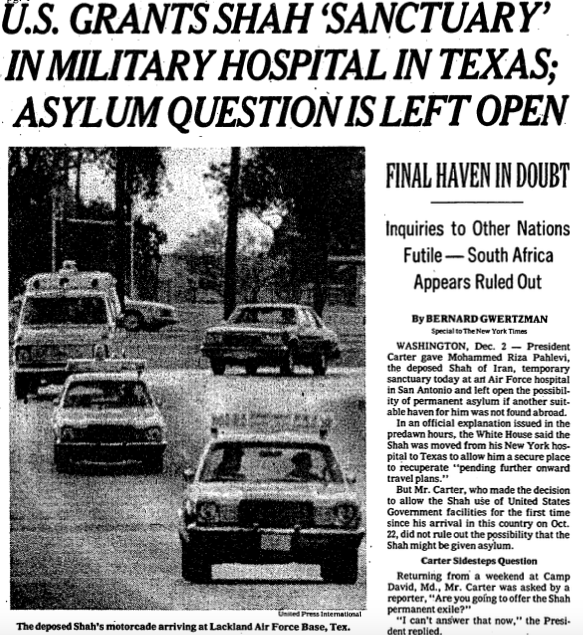

The Shah was presented with three countries that were willing to accept him: Paraguay, South Africa, and ever-faithful Egypt. An American Senator on the Foreign Relations Committee suggested that the Shah might like to go to South Africa because his father had died in exile there in 1944. As the deposed king debated his choices, the U.S. government desperately sought to limit his visibility in hopes of improving negotiations for the hostages in Tehran. It was decided that he would be moved to a military hospital on Lackland Airbase, Texas for the time being.

When Mohammad Reza and Farah Pahlavi arrived, they were ushered to rooms in the psychiatric ward of the hospital. The rooms, Farah reported, had walled-up windows and lacked door handles on the inside of the door. Apparently, they had been given these rooms due to concerns for the monarch’s safety on the base, but the King and Queen worried that the rooms were a sign that the U.S. might have decided to trade them to Iran for the hostages.

Confined to the ward, the Shah’s fate seemed increasingly uncertain. South Africa and Paraguay rescinded their offers. The Shah heard that his nephew, Prince Shahriar Shafik, was assassinated in Paris outside his sister’s apartment. While Prince Shahriar was the first member of the royal family to be killed, the threat and paranoia of assassination hung about them constantly. Princess Ashraf, the Shah’s twin sister and Shahriar’s mother, had survived an assassination attempt when gunmen opened fire on her Rolls Royce in France two years earlier. The revolutionary government had issued a bounty of $143,000 to kill the Shah. During his stay in New York Hospital, a senior U.S. government official announced that Mohammad Reza’s doctors had unknowingly been passing information to the Iranian government. Though no attempt on his life ever materialized, it was also rumored that a so-called “suicide squad” was sent to assassinate the Shah in Mexico.

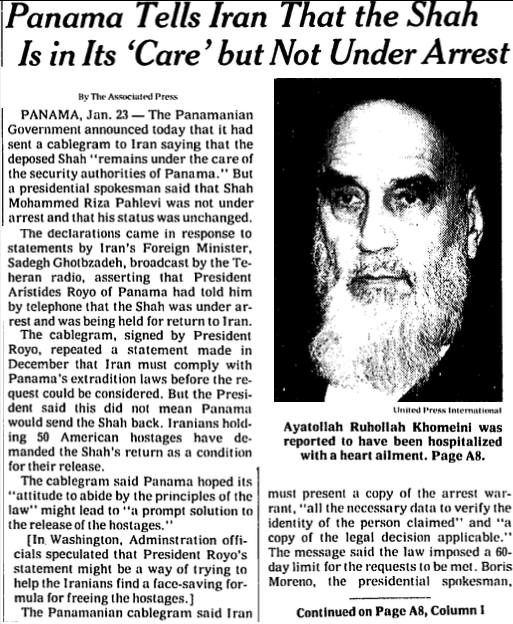

In the bizarre and penultimate chapter of the Shah’s journey, the U.S. convinced Panama to receive the Shah, and populist General Omar Torrijos welcomed him to the island of Contadora. The island would later gain notoriety for hosting three seasons of the popular reality show, Survivor. Even in Panama, protests followed the Shah as leftist student groups called for his extradition to Iran. The Islamic Republic also seems to have employed psychological warfare to encourage the Shah’s paranoia and create distrust between him and his Panamanian hosts. A month into his stay, Iranian Foreign Minister Sadegh Ghotbzadeh announced that President Royo of Panama had told him that the Shah was under arrest and being held for return in Iran. Panamanian authorities were quick to denounce Ghotbzadeh’s statement as false, but the Iranian government had succeeded at heightening the Shah’s fear that his hosts might extradite him or allow his assassination.

The deposed king’s suspicions were not eased by many of General Torrijos’ actions throughout his stay. Perhaps as a joke, Torrijos assigned a professor of Marxist philosophy at Panama University to be the King’s primary host and intermediary for Panamanian security. Torrijos was also known to enjoy spending time with the Shah and lecturing or teasing him about his current state. The general would frequently refer to Mohammad Reza as chupon—an orange that has been squeezed of its juice—and is quoted as saying, “This is what happens to a man squeezed by the great nations… After all the juice is gone, they throw him away.”

Despite the lack of evidence that the Panamanian government had any intentions but to safeguard the Shah during his time on Contadora, he decided to depart Panama in mid-March when he received a letter from Kissinger urging him to leave the country. There were growing concerns for his protection in Panama but the decision to leave came once it was clear that the Shah required surgery and many were uncertain about the care he would receive there.

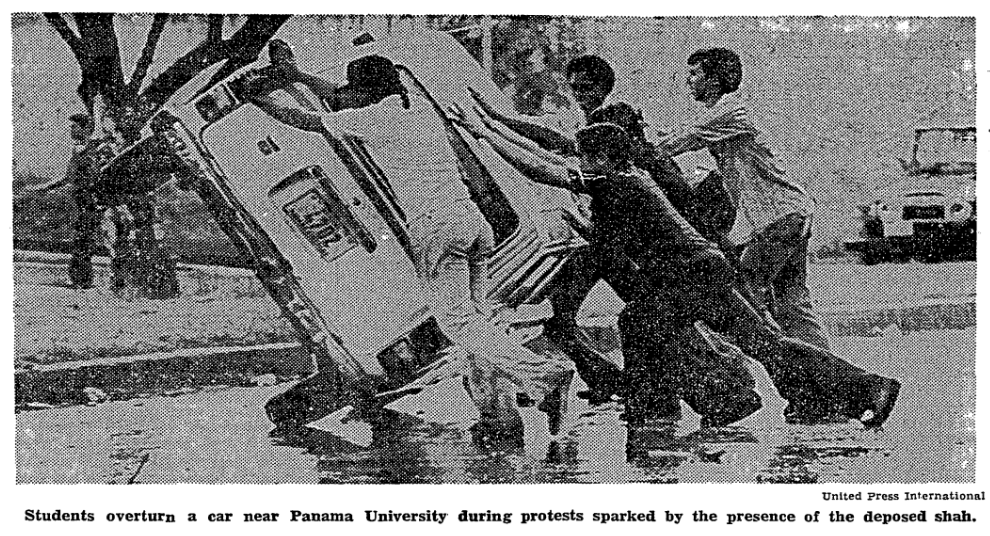

December 21st, 1979 - Protests in Panama sparked by the presence of the deposed shah - The Washington Post

Dying, defeated, and abandoned by most of his allies, the Shah finally returned to where his exile began, Egypt. “The deposed Shah of Iran arrived in Egypt,” the New York Times reported, “looking pale and haggard after an all-night flight from Panama.” Descending from the plane the Shah was greeted by President Sadat, one of his few remaining friends, who had accorded him a welcome befitting a head of state. After being shuffled around the globe and subjected to humiliation after humiliation, the weary despot had finally found a place to permanently lay his head.

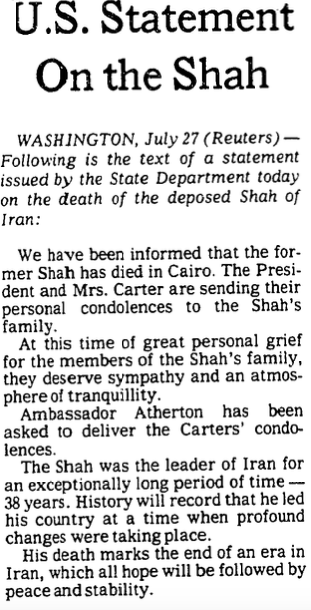

The brief and final Egyptian chapter of the Shah’s exile would be relatively uneventful. The Shah underwent surgery, recovered, developed an infection, had liters of pus and pancreatic debris drained from his body, and recuperated once more. On July 26th, the Shah fell into a coma but was revived later that same day. He regained consciousness long enough for a final farewell to the family that had made it to Cairo. On the morning of July 27th, 1980, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi became the fourth and final king of Iran to die in exile.

***

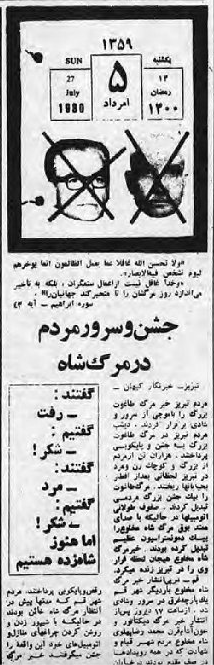

July 18th, 1980 - The People's Celebration and Joy at the Death of the King - Kayhan

Celebrations of his demise adorned every Iranian newspaper in the days following his death, while headlines in the New York Times read: “U.S. Quietly Acknowledges Death of Shah” and “Few Ex-Allies Will Attend Funeral of Shah Today.” The Pahlavi family sent no formal invitations to any world leader for the funeral. No Muslim leader, besides Sadat, would be in attendance. In the year that had passed since Mohammad Reza Shah fled Iran, he had become a pariah on all sides.

The attendees of the funeral convey the isolation of the Shah’s last days. Aside from the ambassadors discreetly sent by a few Western nations, all of the mourners at the Shah’s funeral had been overthrown in one way or another: Constantine II of Greece was ousted by a military junta in 1967; Richard Nixon had resigned in scandal to avoid a possible impeachment in 1974; and, of course, the Pahlavi family was already in exile. While Sadat was not overthrown, little more than a year after the funeral he was assassinated by an Egyptian army officer working with an Egyptian Islamist group—a fate with echoes of the Shah’s own downfall.

Even the mausoleum of his internment was no stranger to deposed monarchs. Awaiting Mohammad Reza inside the mausoleum was another member of this odd class, the deposed King Farouk of Egypt: overthrown in 1952, dead in Italy in 1965, and finally permitted burial in Al-Rifa’i once Sadat came to power in 1970. In a twist of fate, Mohammad Reza Shah would be laid to rest where his father, Reza Shah Pahlavi (d. 1944), had spent six years residing before his body was removed and reburied in Iran.

Sources:

The Shah by Abbas Milani

The New York Times with Index (1851-2016)

The Nashriyah: Digital Iranian History Project at the University of Manchester

Samuel Tafreshi is an Iranian-American writer based in Beirut, Lebanon. He holds a BA in Religion and is currently pursuing a graduate degree at AUB. His work has been published by Khabar Keslan and Ajam Media Collective. A forthcoming piece will be featured in the next issue of Rusted Radishes.