Liminal Belonging

by Bergen Hendrickson

All images courtesy of Tarek Al-Ghoussein and The Third Line in Dubai.

The Al-Sawaber apartment complex was conceived as one of the Gulf region’s first grand utopian housing complexes, designed in 1977 by a Canadian architect during a wave of new construction projects in Kuwait. As just fewer than 500 of the more than 900 apartments were ever built, the project was deemed a failure, and the complex is now slated for demolition. Among the reasons attributed to this failure were the designers’ lack of accommodation for communal spaces within the complex. Notably, according to an essay on the project by Kevin Mitchell, the structure’s plan failed in a few critical respects:

“Beyond the compromises made during the initial implementation of Al-Sawaber, the fact that the space provided in the apartments was only one-third of that provided in single-family homes and the lack of a designated diwaniya—or even the possibility of adapting the dwelling to create a male-only social space to be used periodically—imposed significant constraints. The limited space, at least relative to single-family homes, and the absence of a diwaniya not only affected usability, but also likely impacted the resident’s perception of how they may be viewed within their broader social networks.” (Mitchell)

Nevertheless, Tarek Al-Ghoussein sees the estate as a site that is more significant to Kuwait’s landscape than a mere failed experiment.

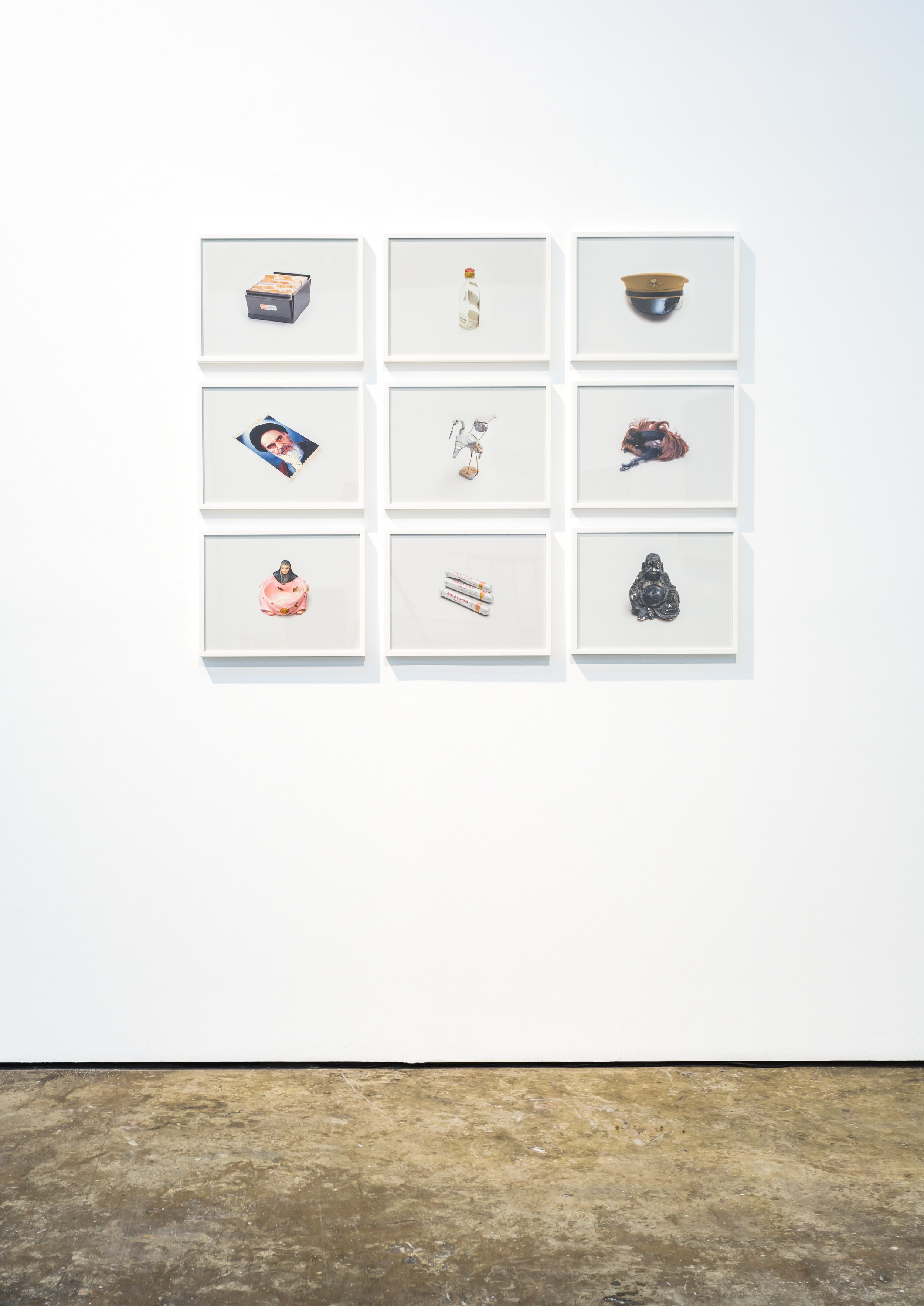

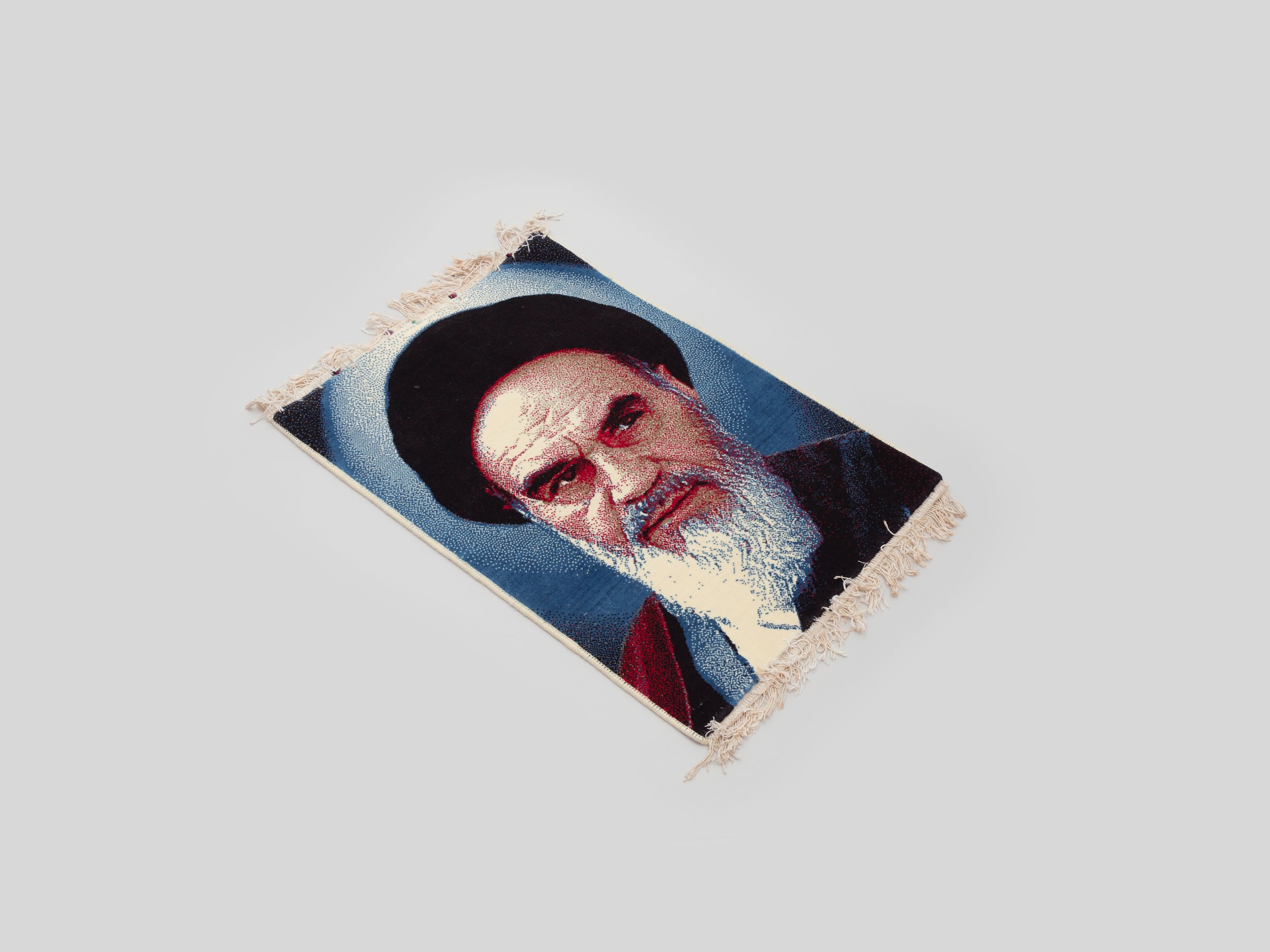

In his latest show at The Third Line Gallery in Dubai, curated by Salwa Mikdadi, Al-Ghoussein photographically indexed some of the archeology of the empty structure. Rather than entombing the past lives of the many apartments he explored as ruinous or overtly civil-political, the spaces are treated as testimony to coexistence and the ways in which people adapt to spaces that suit them poorly. The photographs are devoid of figures, but they attest to life in an active, present-progressive sense: these are demonstrations of the making of a home.

For Al-Ghoussein, it is clear that the home, even when vacant, is a potent symbol for self. Some recent writing has perhaps insisted too much on the existential, Beckettian eeriness of his work, understandable enough given the apparently increasing emptiness of his compositions. This latest development in his practice, however, suggests that Al-Ghoussein’s work has been in an ongoing process of focal-distance shifts, dancing nimbly between the intimacy of portraiture, anonymous human figure, and vast allegorical landscape.

This simultaneity of focus is encapsulated in single photos within this exhibition, such as one work showing a wall with a peeling fresco of some swallow-like birds, a tilted oil painting reproduction, and, subtly tucked at the far left of the photo, an electrical socket. While the architectural surveys in black and white convey the sheer empty magnitude of the complex, every color photograph feels intimate.

Al-Ghoussein’s work is held in the collections of institutions such as The Guggenheim, The Smithsonian, and The British Museum, and he was chosen as Kuwait’s Representative in the 55th Venice Biennale. In his series of photographs in which his figure appears small and anonymous, dwarfed in scale by spacious and empty environments, he straddles the boundary between landscape and portraiture. Not quite abstraction, the figure acts more as a mythical stand in for the individual, and it is in this sense that these photographs feel more like performance than portraiture. While the kaffiyeh that the figure wears both forces some viewers to rethink their immediate associations and identifies a Palestinian heritage, walls and other physical barriers block out access to this heritage. In these photos, Al-Ghoussein acts out an inherited myth of a solitary figure powerlessly struggling for a freedom in relation to home. Al-Ghoussein’s parents were exiles of Palestine, and Al-Ghoussein, born in Kuwait, has reportedly never been able to visit Palestine. Al-Ghoussein’s most recent body of work documenting the derelict Al-Sawaber complex suggests a more subdued, tender continuation of his continued exploration of the space and poetry of a relation to ‘home’ that remains elusive.

Bergen Hendrickson is a writer and curator currently living in New York City. His recent work has centered on American outsider artists and the problematics of such contemporary art categories, and artists’ peripheral activities. He is also currently working on curating a group show examining the legacy of European futurism and Boris Groys’ theory of “rheology,” slated to open in Spring, 2018.