Before We Were Banned

by Azmi Haroun

From left to right: Kiana Pirouz, Farhad Barham, Soraya Majd, Asiya Al-Sharabi, Tandis Shoushtary, Carmen Daneshmandi, Gina Malek, and Mahya Soltani. Photo by Jack Newton.

Before We Were Banned was an independently organized art exhibition featuring artists connected to countries included in Trump’s Muslim ban 1.0. The exhibition took place in NYC from January 26-28, 2018, and featured over ten artists—Mays Albeik, Layali Alsadah, Asiya Al-Sharabi, Farhad Bahram with Tom Lundberg, Carmen Daneshmandi, Ibi Ibrahim with Hosam Omran, Rhonda Khalifeh, Soraya Majd, Gina Malek, Ifrah Mansour, Tandis Shoushtary—with heritage from Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Iran, Syria, Yemen and Iraq. The curators, Brooklyn-based Iranian duo Mahya Soltani and Kiana Pirouz, joined forces to celebrate these communities and repudiate these nations’ antagonistic image in the United States. These days, they are planning to take the show on the road to a few cities on the west coast. They’ve also built a community of Iranians in NYC that they plan to keep growing. Khabar Keslan is proud to present six interviews with the curators and artists alongside this review.

Seeing shared struggles in the wake of the Trump administration’s series of “Muslim Bans,” Kiana Pirouz slid into Mahya Soltani’s DMs. Kiana is an artist and marketing executive who moved to the US from Tehran at a young age, and promptly showed up to JFK to protest the initial ban on January 27th 2017. Mahya, a graphic designer and MFA student at the School of Visual Arts, had moved to the US from Tehran just four months before the executive order was signed.

For Kiana, the order was a continuous reminder that she “didn’t have any Iranian or diasporic friends to relate to.” Mahya felt the same way, and, once the two women met, they realized that they shared similar goals to foster a sense of community. Shortly after connecting, they organized a Persian New Year feast and saw potential for broader restorative projects through friendship and collaboration.

In a twist of irony, their shared “familiarity of feeling alienated in the United States and in our home countries” brought them together. Drawing on her expertize from the media industry, Kiana grew concerned as to who was telling immigrants’ stories. Who owns the narrative? Who helps heal these terrified communities? This suffocating uncertainty led Kiana and Mahya to the idea for a “Before We Were Banned” group art show. “We wanted to highlight that these communities have been oppressed and marginalized long before this ban was imposed,” Mahya told me. They sought to foster “a community or a collective that not only exhibits work together, but can connect through their experiences.”

Although this venture was Mahya and Kiana’s first in art curation, they had clear goals. With the intention of celebrating the breadth of immigrant narratives, they “hoped to build physical and emotional space for artists affected to tell their stories, unfiltered,” says Kiana, “a respite from having to explain one’s story.”

The exhibition’s open call and mission statement point to the warm environment Kiana and Mahya created from the outset. The call was extended to US-based artists with a connection to the seven affected countries. Kiana and Mahya encouraged the artists to change the narrative “from the inaccurate, antagonistic image so often portrayed,” with the aim of shattering “the persistent duality of life as an immigrant in the United States: pursuing success and thriving while made to feel unwelcome and misunderstood.”

***

Walking into Before We Were Banned was a diasporic homecoming—an exercise in memory beyond borders. Picking up a customary cup of tea, I gravitated towards Layali Al-Sadah’s piece Blood at War, featuring a battered American flag with English and Arabic inscriptions. The flag itself, stolen from a Walmart, was a canvas for words like “threat”, “radical”, “targets,” and “collateral damage,” transposed by the repetition of the phrase, in Arabic, “Oh lord, please save my country Yemen.” As a Syrian-American, I found solace in the Yemeni-American artist’s rejection of this language, which exists to subdue and marginalize non-white Americans. The flag exposed America’s shallow patriotism, as Layali notes that, on one hand, the US government “covertly supplies military funds to the conflict in Yemen” while simultaneously engages in the “closing of the border to fleeing civilians seeking refuge.” Layali loudly and proudly interjected her narrative in a society that is silent on the US role in terrorizing Yemen through a space tailored to uplift her voice.

While viewing this piece, I also overheard an amusing conversation that reflected the all-encompassing space Mahya and Kiana had successfully created. Two attendees of Yemeni origin were reminiscing about past trips home when one of them excitedly admitted, “Okay, orientalism aside, Yemen is so exotic.” I smiled to myself, realizing that I was somewhere with complete fluidity and comfort with our definitions of home.

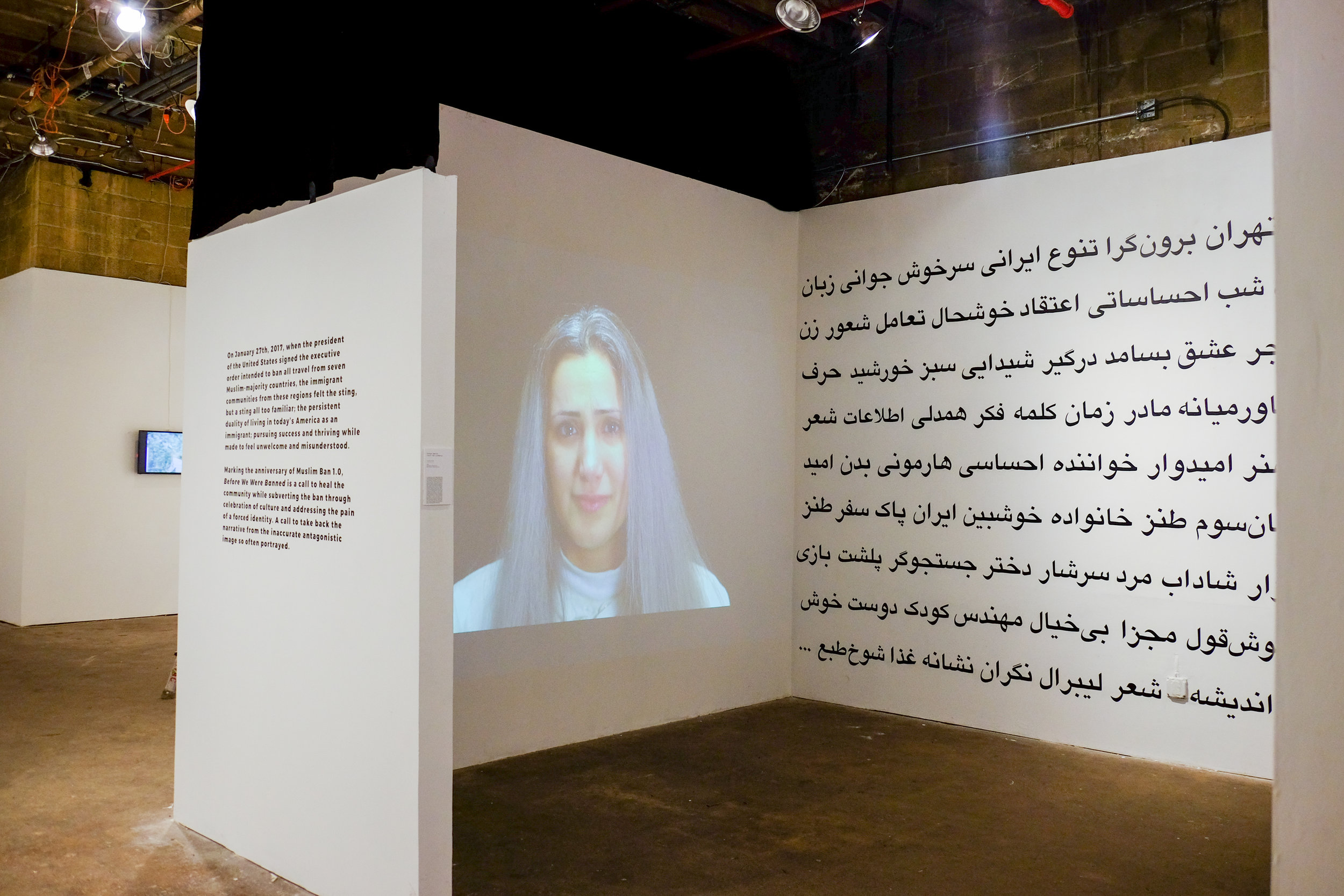

I wandered into Farhad Barham’s Farsi-laden audiovisual installation with curiosity and building giddiness. I was immediately struck by the power of being in a room steeped in words from my grandmother’s native tongue. Two walls were covered with stand-alone phrases and words like “immigration” and “home” in Farsi, with a muted video projection on a third wall featuring participants sharing “a list of words that represent their individual identity.” Imagining the discomfort that the visual experience caused for other non-Farsi speakers made me even more comfortable. Though I do not speak Farsi, I appreciated Barham’s pointed use of language to force viewers to engage “with people they can’t completely understand and cannot reduce to a label.” Farhad welcomed attendees into the space, and his work reminded us that the subjects’ “words, images, and presence cannot be labeled or banned.” Having visited Iran once in the last seven years, his work was a much more nuanced window into discussions about Iranian identity that disregard American and Iranian political narratives.

BWWB artists explored their connections to Iran in varied ways. Tandis Shoushtary, a graduating student at Cooper Union, was “trying to navigate the dissonance between western and non-western contexts encountered when the culture and language of familial roots are learned in settings of migration.” Having visited Iran just once, Tandis was wary of being defined solely by her Iranian identity even before Trump's election. Tandis' piece Mother's Tongue was, as she says, an honest response to the "instances of misunderstanding and miscommunication that occurred when I visited my ‘home country’." To “reclaim, remember, and editorialize a specific connection to the Iranian passport,” she meticulously painted 800 frames of home video footage from her trip to Iran. One look at a single frame forced me to think about my own connection to Syria, much of which lives through memory and photography. Through muddled noises of children screaming in the courtyard and aunties with accentuated, thick eyebrows politicking in the living room, Tandis’ struggle to assert herself as a first-generation immigrant while embracing identity through family roots deeply resonated with me.

BWWB was Carmen Daneshmandi’s first New York show. The daughter of a Spanish mother and Iranian father, Carmen describes her mixed identity as something that she feels “very deeply for but also feels at a loss with.” She laments not knowing her Iranian heritage well enough, and detests being devalued because of that heritage. BWWB created a space for her to heal, reflect and voice her narrative in her own terms. The result was a set of individual collages, which brought the viewer very close—her mustachioed male relatives in the car, her grandmother in a warmly lit olive doorway, transposed with background photos of Iranian landscapes like mountains, a smoky highway, or a rug that serve to build “family legacy and ancestral legitimacy.” Though the photos she used in the backdrop were less intimate, they showed how daily life is broken down into mundane and familial elements, which structure our shared identity. I recalled the countless summers in cars in Yaafour, Syria, trying to make sense of the juxtaposition of arid mountains and rusted cars emblazoned with Hafez and Bashar Al Assad’s faces.

Diasporic merchandise from Fully Booked, artist Taravat Talepasand and musician Yassin Alsalman AKA Narcy were also featured throughout the weekend. I floated around proudly wearing my favorite “Islamic Youth” T-shirt, made by Taravat. I’ve worn the shirt in plenty of places, and have been served looks from brunch tables to TSA lines—but wearing the shirt at BWWB was cathartic, and not solely defiant.

Reflecting on the tugging and strange associations with home as a diasporic individual, BWWB furthered the conversation about how our collective alienation and discomfort with our relationship to home is what relates us to each other. Iranian pop legend Googoosh was blasting during the event set-up and, on the last day, an attendee used one of the exhibition rooms for prayer. Mahya and Kiana intentionally did not label artists’ work based on their nations of origin; instead, the artists’ own narratives shined. To be seen and validated, a year after being collectively and arbitrarily banned, was a critical step in rejecting the currents of history and defining our own identities. Before we were banned, our narratives were constricted in a multitude of ways, but Kiana and Mahya provided a space to breathe and imagine a future we deserve.

INTERVIEWS

Kiana Pirouz immigrated to Atlanta, Georgia from Tehran, Iran at the age of 3. After attending the University of Georgia with a degree in Journalism, she has spent over a decade working in media and marketing in New York City. Fusing her interests (music & art) with her knowledge (media & immigrant life experience) in her personal work, Kiana is focused creating strategies and avenues for the marginalized to maintain and spread their authentic narrative while leveraging the tools of mass media to ignite cultural conversations and illuminate real stories.

Born in Tehran, and raised between Tehran and Dubai, Mahya Soltani is an Iranian designer and visual artist currently residing in Brooklyn, New York. After practicing as a designer and an art director in Dubai, UAE for four years, Mahya moved to United States to pursue her MFA in Design Entrepreneurship at School of Visual Arts in New York. Her practice as an artist engages time as a tool challenging expectations and perceptions while delineating the existence of alternate realities.

Tandis Shoushtary is a German-born BFA student at the Cooper Union, who learned the culture and language of her (Iranian) familial roots in the context of migration. Her work investigates the shaping of identity and its hybrid forms resulting from relocation.

Carmen Daneshmandi is a photographer & visual artist based in New York by way of Seattle but also by way of Spain and Iran because that is her makeup. Driven by the texture of identity and the cultural backbone that holds you, her work spans to celebrate and carve out space and visual capital for people of color and the pulse of their evolving narratives across audio-visual vignettes, portraiture, and mixed media collage. As she questions these current representations, she uses powerful juxtapositions, identity through object, mental health, and abstractions of personal history to guide her.

Ifrah Mansour is a Somali refugee Muslim multimedia artist residing in Minnesota. She explores trauma through the eyes of children shedding light on the resilience of black, Muslim, refugees. She interweaves text, movement, and digital media to create a multi-sensory artwork that illuminates the invisible stories of immigrants. Upcoming works include My aqal two, Can I touch it at Minneapolis Institute of Arts, and How to Have Fun in a Civil War at Guthrie Theatre.

Soraya Majd’s work revolves around identity and memory. As an Iranian-American she uses both photography and printmaking to work against the cultural erasure that comes with growing up in the Persian diaspora. For her, the investigation and research that goes into planning a piece is just as rich a part of the process as creating the piece itself. Constantly inspired by her family’s photo albums, she weaves together portraits and Persian design elements to create space for what is lost to political division.

Asiya Al-Sharabi is a Yemeni artist. She started as a journalist photographer then shifted to the art scene detailed and descriptive. As a middle Eastern female artist, she faced many challenges during her career as a photographer, but she has also turned her lens to art photography in an effort to capture the energy and personality of Arab women who are, through cultural strictures, not allowed to be photographed. She uses a self developed technique that expresses and focuses not only on aesthetics, but also on the underlying struggles of women surrounded the world. Her work questions the effect of culture and religion on female identity.