My First Pet or The Personification of Vermin is a Cure for Loneliness

by Sandra Esmeralda De Anda

(She/Her/Hers)

Original artwork by Olivia Chapman (@bugdumb).

Felipe flew first class in a Ziploc bag lodged between Dodger memorabilia and a handful of 50 cent soaps my family bought at the Santa Fe Springs Swap Meet. My mother also packed so much underwear in my suitcase that her gesture felt political. I was still getting used to having my period, so this gesture felt like a great declaration of my womanhood but not of my independence. She made a great fuss about not wanting me to stain myself in front of the bourgeoisie. (The bourgeoisie did not stain themselves because they wore tampons, but my mother did not want to acknowledge this.) She said if I lodged a cotton phallic-shaped object into my body, I would defile myself, and that would not be Catholic of me. This gesture tucked itself silently inside my body as I waved good-bye to her at LAX while ascending the stairs to my airline gate with my father. Her eyes swelled with tears. I was the oldest daughter, after all. Sometimes the only distinction between me and her had been that she had birthed the children that would then become mine to raise.

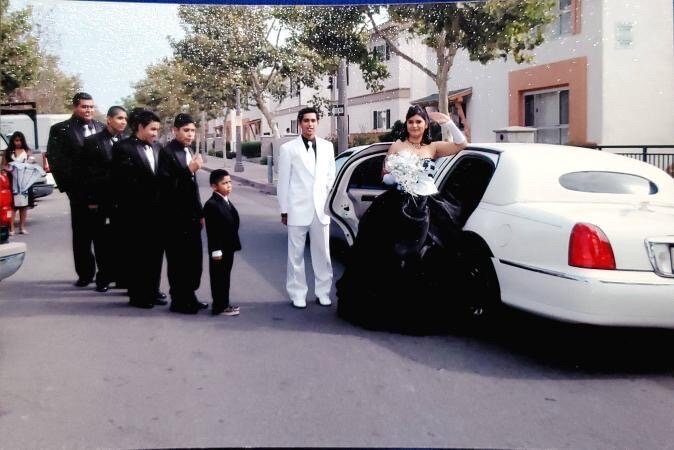

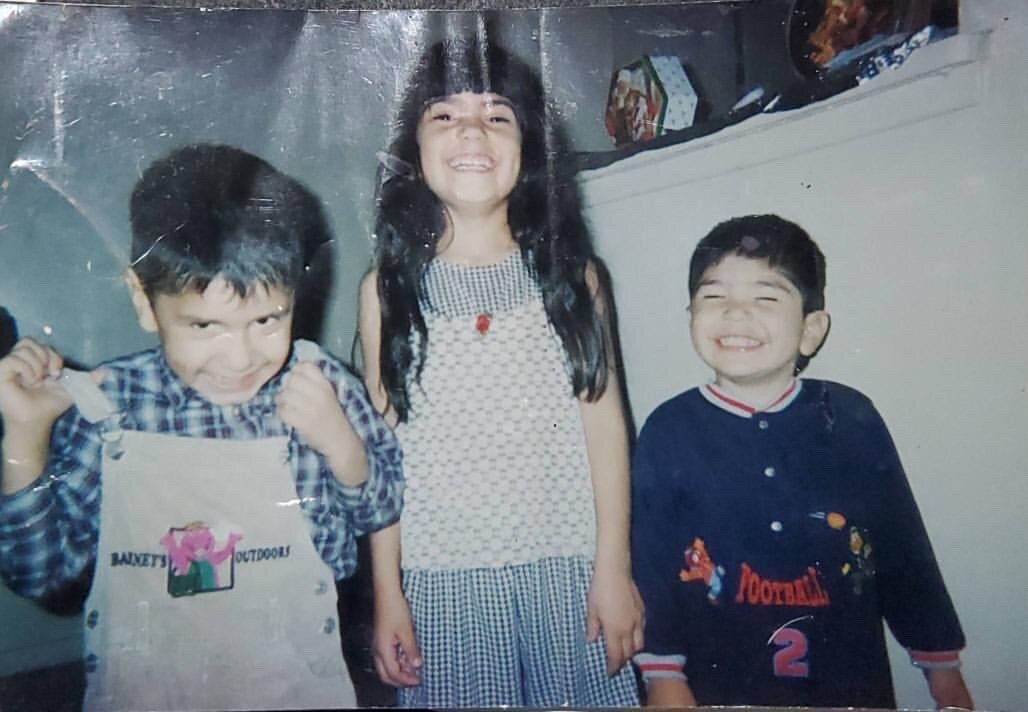

Courtesy of Sandra Esmeralda De Anda.

Throughout the entire plane ride to the all-girls boarding school, I tried to think about my mother’s best qualities, archiving the memories where she’d lean over to tell me all these wondrous tales of La Concha, a Sinaloense pueblo ten miles north from the Nayarit border. This pueblo can only be compared to Juan Rulfo’s depiction of Comala in his work Pedro Paramo: “That town sits on the coals of the earth, at the very mouth of hell. They say when people from there die and go to hell, they come back for a blanket.” She would tell me the tale of Berenice, my grandfather’s pet crocodile, who she says became jealous of my grandmother. The young crocodile showed a certain warmth towards my grandmother in her young age, gesturing her body closely to hers like a feline. In its maturity, though, the crocodile became so jealous of my grandparent’s relationship that she tried to bite my grandmother’s leg off while she was sweeping the backyard when no one was home. Berenice was shot when my grandfather came back from corralling the pigs that day. “This is what happens when a man names his crocodile after his wife,” she tells me with her beautiful smile, two peaks of Kilimanjaro. Every time she gets done with the crocodile story, she tells me the story about the birds that my father freed at a local zoo in Mazatlán, and the story about my grandparents dancing Cuban Mambo in Santa Ana in the 1950s, at the height of the McCarthy Era. She gives a home to all these stories, and to this day they rain from her tongue like scripture.

The plane landed in Greensboro, North Carolina, and my Father, Felipe, and I were greeted by a white man holding a placard that read my name. He motioned us to a van in the parking lot and placed the luggage in the trunk. My father sat in the front seat and spoke to our driver, who had a southern accent and a big frothy mustache. I sat in the back seat, my body a furnace in a Dodgers jersey. I marveled at all the green trees, the sticky weather, and the soundtrack of the cicadas. It was overwhelming to feel so special, yet so alone. The two-hour ride to my new boarding school proved to be an exercise of letting go.

The frothy mustached driver drove the van up a hill. He picked up my luggage and directed me towards the entrance of a gigantic, pillared building that felt like something out of a Louis Malle film. My father and I arrived bug-eyed and brown. We were greeted by sweet tea, Burberry-breathed southern accents, white girls in bright pink Lacoste collared shirts, and cucumber sandwiches, so small I kept asking for the main course. I carried all my belongings, including my pet and one suitcase with all the things I had accumulated those 13 years of living in Santa Ana, to my dorm room. I trembled, realizing this was my new home. I would miss plucking the blue gumdrop eyes off the Paleta Payasos and gobbling them up, talking to my crush for countless hours on a landline working on homework while my parents looked at me indignantly, and tying strings to June Bugs to fly them around like summer kites with the other children. There were things I wouldn’t miss too: Grown-ass cholos hitting on me, the slaps on the head for coming back home late from a pentathlon meet, & the marimacha / lesbiana descriptor that sat on everyone’s lips when I rode my skateboard by them. Amid this introspection, I looked at my dad’s face, a place of many rivulets, though I had never seen him cry. “Mija, pues ya me voy. Cuidate y echale ganas.” I began to cry when I heard him say these words to me. I knew he had to catch a flight back to Southern California to be with my mother and siblings. He could not stay long for the machines and those who own them would not allow.

Courtesy of Sandra Esmeralda De Anda.

I sat alone in my dorm room with my feelings: mushy feelings, noisy feelings, fickle feelings that evaporated when they came into existence, and feelings that became figs that I devoured before they devoured me. I realized in my bewilderment that I was not completely alone. I opened my suitcase and found Felipe eating Teddy Bear Graham crumbs. His body glistened through the Ziploc bag and I pulled him out with a string I tied around his leg. I had always wanted a dog but the managers in our apartment complex prohibited it. I adjusted easily to the limitation, which inevitably led me to appreciate walking Felipe’s little cockroach body. I never pet him or groomed him. (I guess my religious upbringing taught me to appreciate these metaphysical notions of love: Nothing gets consummated, but the distance between us replaces rejection with thoughts of the sublime.)

Courtesy of Sandra Esmeralda De Anda.

The entire week before school began, I spent most of the time evading orientation activities. I had originally intended to try out for the volleyball team, and I did for 3 days out of the 7, but quickly became reticent as I realized that the girls I was competing with were professionally trained. The most physical training I ever had was handball games I played to win chili-covered crickets at recess. I felt like a cricket at that moment, seemingly small with so much to say in the darkness. I hid in my dorm room and skipped meals in exchange for more time with Felipe. I walked him around different surfaces, desks, and tables, where at times I would draw small backdrops for him, so it looked like he was walking on sandy beaches or observing architectural feats. This creature served as a pocket where I had put my loose change, my sadness, my culture, and my doubt.

The last day of orientation week, we spent Sunday afternoon with a backdrop of Santa Ana, our home. I drew the Water Tower in Downtown. I drew North Bristol Street full of low riders and Mexico soccer fans. I drew Main Street and the pupuseria where I would later reenact scenes from Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together with my first true boyfriend, one who treated me more than just a fixture in their life. Our excursion was interrupted in the evening by inching footsteps. I shoved Felipe into the first cabinet of my desk. My new roommate and her mother walked into the room, bowed, and gave me a stationary gift. I asked Jenny where she was from and she just said, “Korea.” I, 13, I with the fancy-ass scholarship, I an individual who strategically spent time asking Jeeves instead of playing Frogger, asked her if she was from the North or South. Four eyes laid on me and sighed. I did not get it; I just felt the air thicken. Only a few years later did I understand my faux pas and I too sighed.

And only a few years later did I become ashamed of the Felipes, little galaxies that would gather at night to eat the crumbs of our unrinsed plates. I would exterminate them the night before a friend would come have dinner or spend the night. I was ashamed to have them know about all these inhabitants who I used to find solace in.

*

I prized the one Felipe I had. He was a fancy fool like me, but like all fools and even sages, Death traps them. It was mid-November when Jenny accidentally stepped on him on her way to her third-period class. She thought it was a cicada that climbed through our window, a foreign body. I blame her sleepiness for how the series of events unfolded. The lifespan of a big cockroach is a year. The lifespan of a big, domesticated cockroach in a bourgeoisie setting is 3 months. I often wonder if I should have just left him at home with my siblings or at a nice diner; there, he would roam with its complexities and potential the way Kafka could only begin to imagine. A salesman, selling and sailing on crumbs leading to another bug-eyed girl.

Courtesy of Sandra Esmeralda De Anda (bottom left).

Sandra Esmeralda De Anda is a non-fiction writer, standup comedian, and cultural and political critic. She is currently the Program Coordinator for The Orange County Justice Fund, an immigration bond fund. Her writings have been featured in The Voice of OC, The OC Weekly, Makara Arts, and Longleaf Review.