Why You Should Bother to Visit Exhibitions

by Ali D.N.

All photos by Ani Çelik Arevyan, with courtesy of Ani Çelik Arevyan, Antonio Cosentino and İbrahim Cansızoğlu.

An account of a series of events from 7-21 October 2017, which revolved around an exhibition

I take the ferry and reach Karaköy. I pick up a couple of wireless extender devices along the way for 40 liras each, because why not. I climb up the steep streets to get to Galata Tower and ask people around for the “Hamursuz Fırını,”[1] the old factory that used to make unleavened flatbread (matzo) for the Jewish community. After receiving a few contradictory directives, I look at Google Maps and ashamedly hold my phone screen as close as possible to my chest. Finally, as I walk down a chaotic, dusty and extremely noisy street with construction crews all over, I see a little yellow poster that points left and reads “Protocinema Presents: For Rent, For Sale.”

I pass a warehouse-like space of a construction site, and spot a couple of artsy-looking people. The young man gently greets me in Turkish, and the woman sitting next to him shouts a confident and enthusiastic “Hi!” I’m mainly interested in the exhibition, which my friend, İbrahim Cansızoğlu curated, so initially make no more than a customary effort to reply to their kindness.

The machine of the old bakery behind Antonio Cosentino’s table installation. According to Mari and Melih, the bakery stopped running a few years ago when imported bread from Israel became cheaper. The machine might still work, but they think it would not be safe to run it.

After I view the exhibition, and the woman asks me if I went upstairs. I reply that I’m unaware of what’s upstairs, so she takes me to experience the second exhibition above, which screens the work of Adrian Paci: a most moving montage of footage showing the state funerals of dictators. That is how I unknowingly met the founder of Protocinema, Mari Spirito.

We sit and chat for a bit along with Melih, “a member of Mari’s Ocean’s Eleven in Istanbul.” We talk about how Mari founded Protocinema and carried it into a global success. Protocinema, “named after a Werner Herzog observation of cave drawings,” organizes “site-aware” art events in New York, Istanbul, and Delhi, among other cities. “We arrive at a city, we build a network, and make stuff happen,” says Mari, and I couldn’t agree more.

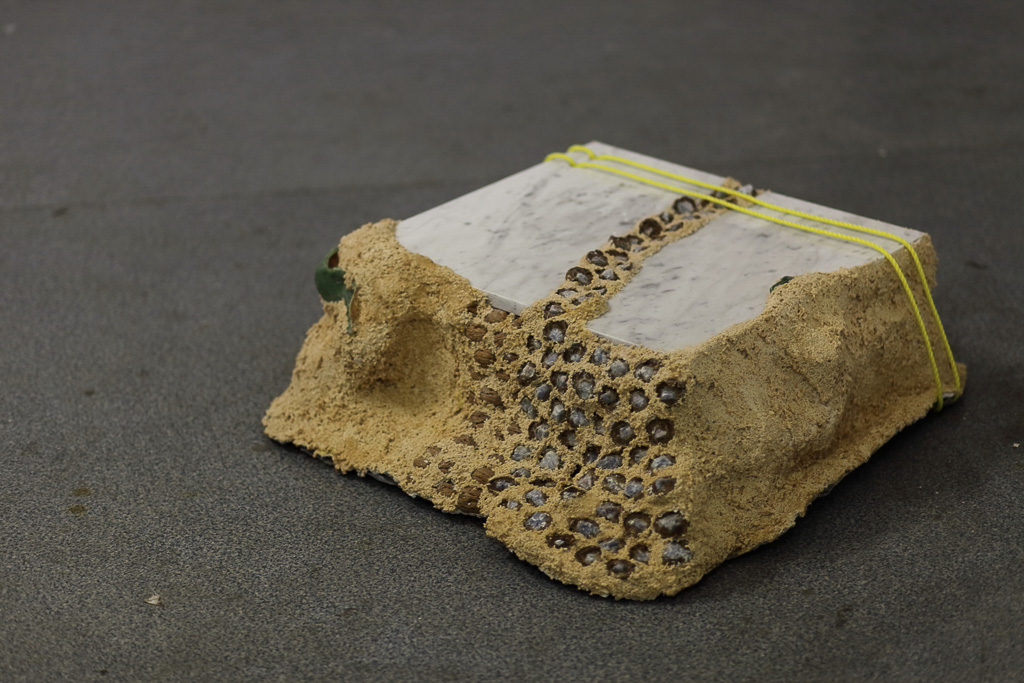

I observe and admire the highly intriguing and meaningful installation, made of materials including limestone commonly known as “Istanbul stone,” by Gülşah Mursaloğlu. I am moved as I view Ani Çelik Arevyan’s photographs and see what she means when she says in an interview that she “does not take but make photographs,” and that the photos form a sort of timeless “storyboard” of her life. The voices of Istanbul, taken from “The Sounds of Istanbul” project, adds a sense of memory to the atmosphere, which feels as if I am lucid dreaming of a lost city that once sounded blissful, carried unique smells of various kinds of bread, built urban artifacts not from cement and concrete but from fitting local materials, and had a distinct history to its landscape. Now, it is lamentably “for rent, for sale.”

Detail of the installation by Gülşah Mursaloğlu.

Antonio Cosentino’s portion is also intriguing, but I don’t quite get it. There are a few drawings of old vehicles, a reading corner composed of a “carefully chosen red plastic chair” and a second-hand, wooden end-table, and a variety of interesting little objects on a table. I later learn from İbrahim that the viewer was supposed to read a short story by Antonio Cosentino placed on that reading corner. Antonio later told me that the objects were “impromptu appropriated additional elements”[2] to the story. As I talk with Mari and Melih, I learn that they ran out of copies of Antonio’s story, so I sort of had an incomplete viewing. Ah!

The objects on the table included many soda caps, old photo albums of travels, an old map book, ceramic bowls, an old cassette player, a model of a building complex and toys of a plane and cars.

I meet with İbrahim and talk about my visit to the exhibition. He says that he will send me the story, and suggests that he track Antonio down and arrange a meeting. I am thrilled at the idea, but he cautions me that Antonio is “kind of a fugitive type,” so I might have to wait a couple of weeks.

After a couple of weeks, we meet on a Saturday night at 7.30 pm at a bar called “Muaf.”[3] Before we met, I was talking with a close friend of mine. He recognized the name Antonio Cosentino as vaguely familiar. He remembered that his mother and Antonio went to the same high school in Yeşilköy, a neighborhood where a portion of the ethnic minorities of Istanbul had moved after the discriminatory taxations and displacements thrust upon them by the state in the late 40s. According to my friend’s mother, Antonio “used to write stories out of thin air.”

We plunge into an endless weave of conversations about Schopenhauer’s aesthetics, Foucault’s concept of “Parrhesia,” “Alethia,” and “Cynism,” and the sadly underappreciated and impressive history of painting in Turkey. An incredible amount of literary references are made, most of which I can’t begin to keep up with. Antonio is an installation artist, but tells me that he has recently (re-)found a will to write. He had received his first education in art in Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University. According to İbrahim, his “magnum opus,” is “the Istanbul Atlas” series of photographs, which consists of thousands of images of different districts of Istanbul, taken over the course of twenty years. Take it from me, Antonio can also tell a tale or two.

After 5+ years of living abroad, I recently moved back to Istanbul, a city of over 20 million people. To be honest, it’s been a bit rough. The number of friends I have here had significantly diminished. I found the city in much worse shape than I had left it. Living here has become an almost impossible task, due to inflation, overpopulation and pollution. Construction work is every-fucking-where. I don’t even have to mention the politicians, who don’t even know what else to do with Istanbul other than put it up for rent or for sale, by building layers of concrete mixed with earthwork on top of it over and over again in a useless, fetishized manner.

Viewing an expression of feelings similar to mine, talking with the artists over these issues, finding emotional and conceptual commonalities, and listening to a few so-funny-that-it’s-unreal stories of the previous generation of Istanbul’s crazy artists over a few drinks have made things a bit better for me, to say the least. The next exhibition you visit might just be the railroad switch that takes your life to the better lane. Just remember to pick up a couple of wireless extender devices along the way.

Ali DN is a writer and an editor. His research interest is mainly the history of religions and politics in the early modern Ottoman Empire. He is a graduate of Reed College, and holds an M.A. degree from SOAS. Born, bred and based in Istanbul.